Literature

Literature

In his compendium Culture and customs of Afghanistan (2005, pp 82-3) Hafizullah Emadi stresses the tolerance that was exercised after the Muslim conquest of Afghanistan in the 7th and 8th centuries:

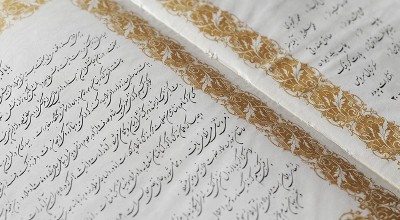

'Islam did not sanction the destruction of the arts and cultural heritages of others, and in this spirit of tolerance worked to adopt and refine some of the ancient traditions to suit the needs and requirements of the new Muslim community. Arab domination of the country caused writers, poets and scholars to use the Arabic language in expressing their ideas and thoughts, and Arabic became the medium of communication in the administrative domain. Although writers and scholars wrote in Arabic, the common people continued to speak their own native languages… The Persian language adopted the use of the Arabic script and it is chiefly due to this reason that there are no written documents in the Persian language during this period.

Arab domination lasted over 200 years until nationalist movements put and end to its influence. During this period, the Persian language gradually established its dominance, to the extent that various rulers promoted the Persian language as the medium in their courts…'

One of the most important works of the latter period was the Persian epic poem Shahnamah (‘The Book of Kings’), completed in 1010 by poet Abdul Qadim Firdawsi and comprising 60,000 rhyming couplets. Writing more than 200 years later, Mawlana Jalaluddin Balkhi (1207-1273), a native of Balkh better known as Rumi, became one of the greatest Sufi poets writing in Persian.

Research on Afghan literature tends to focus on Persian/Dari and Pashtu, and as a result there is relatively little awareness about the wide scope of works written in minority languages. Poets abounded in all strata of society and held respected positions in every community, rural and urban. However, since much of the population in the last century were non-literate, literature per se was largely confined to the urban elite. Dari traditionally dominated, but concerted efforts to revitalise Pashtu were made throughout the last century. Other regional and linguistic groups had rich oral traditions but occupied a minor place on the national literary scene. The 17th-century Afghan warrior-poet Khushhal Khatak (1613-1694), who wrote in Pashtu, is regarded today by many as the national poet of modern Afghanistan. His theme of the noble tribesman later became popular with other writers, and the ideal personality in Afghan culture remains the warrior-poet.

Twentieth-century Afghan literature is eclectic, with influences from Iran, India, central Asia, Europe, and the US. The synthesis, nevertheless, is uniquely Afghan, and often involved with revolutionary attitudes. And, because of the absence of a mass literate audience and a paucity of publishing facilities - which were predominantly government-controlled - writers were largely limited to journalistic outlets.

The first modern Afghan literary luminary was Mahmud Beg Tarzi (1865-1933). After more than 20 years of political exile in Syria and association with reform-minded Young Turks, Tarzi returned to Afghanistan to edit the Dari bimonthly nationalist newspaper Seraj ul-akhbar (1911-1919), in which he argued for Islamic unity, social justice and internal reforms. His translations, including works by Jules Verne, both introduced the elite to new ideas and recommended prose as a viable literary form.

A period of reform (1919-1929) initiated by Tarzi’s son-in-law, Amanullah, ended in a rebellion led by conservative fundamentalists. In the following decade and a half of recovery, romantic escapism replaced calls for reform. Writing in a neoclassical style in the tradition of 11th-century Persia, poets glorified nature and extolled optimism, Islamic idealism and aesthetic values. Abdul Ali Mistaghni (1874-1934) wrote proficially in a wide number of classic poetic forms, in Pashtu as well as Dari. Sufi Abdul Haq Beitab (1888-1969), who became poet laureate in 1942, wrote eulogies to patriotism and mysticism in Dari, following the style of Mogul India’s Abdul Qader Bedel (1644-1726).

When tentative moves toward democracy were initiated in the late 1940s, the poets responded with themes of sentimental socialism. They combined the mysticism of India’s Rabindranath Tagore with Maxim Gorky’s revolutionary championing of the common people. Abdur Rauf Benawa (1913-1984) and Gul Pachta Ulfat (1909-1978), writing in Pashtu, best represent the period from 1946 to 1953.

Among various nationalistic and social topics, they addressed themselves to the restrictions on women in Afghan society, Khalilullah Khalili (1908-1987), who continued the neoclassical Persian tradition, published the first anthology of contemporary authors, Muntakhabat-i-ashur ('Selections of Poetry', 1954). Abdur Rahman Pazwak (1919-1995) employed the same style to explore contemporary problems, idealising the past through his histories and retellings of folklore.

A burgeoning group of leftist writers gathered around Noor Mohammad Taraki (1917-1979), a journalist, novelist, and short story writer who was influenced by the social-protest novels of Theodore Dreiser, John Steinbeck and Upton Sinclair. Suleiman Layeq (b 1930?) and Bareq Shafiyee (b 1931), poets in both Dari and Pashtu, exemplify the development of these activists. Initially they wrote religious poems, but after 1953, when the Shah of Iran was installed, Afghan poets were much influenced by the leftist literature produced underground or in exile by writers of the outlawed pro-Soviet Tudeh Party. This new wave of Afghan writing was heavily imbued with European socialist and existentialist forms, and the ideas of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, blended with Sufi Islam.

Other innovators include Mahmud Farani (b 1930?), perhaps the major experimenter in rhyme and metre, and Mohammad Rahim Elham (1931-2003) and Saaduddin Shpoon (b 1933), who have equal facility in both Dari and Pashtu, in prose and poetry. Zia Qarizada (1922-2008) made major contributions with the poems in Ashur-i-nau ('New Verse', 1957), written in Dari. The female writer Kubra Mazhari (b 1950?), Dari poet, novelist, and short story writer, edited the literary magazine Erfan in the 1970s.

Prose as a mode of imaginative writing gained respectability in the 20th century, but the novel and the short story remained nascent.

Young leaders in the field of short-story writing included Hassan Kaseem (b 1944), Ghulam Ghaus Schodjaie (1940-1979), Sharifa Sharif (b 1953), and Spozhmai Zaryab (b 1949). Their works dealt realistically with everyday contradictions inherent in a society in the process of modernisation.

There is also a distinguished group of prose writers in history and philosophy, mainly in Dari. Among these are Ahmad Ali Kohzad (1915-1983), Afghanistan’s first archaeologist, who wrote Afghanistan dar Shahnama (‘Afghanistan in the Shahnama', 1976); Said Qassim Rishtya (1915-1998) author of Afghanistan dar Nozdah-quran (‘Afghanistan in the 19th century’, 1958); leading socialist historian Mir Ghulam Mohammad Ghobar (1899-1978), who wrote Afghanistan dar Maser-i-tarikh (‘Afghanistan’s path through history’, 1968); Hasan Kakar (b 1932), whose Government and Society in Afghanistan (1979) was written in English; Abdul Hai Habibi (1908-1984), historian of Pashtu literature; and Bahauddin Marjooh (1928-1987) and the afore-mentioned Ghulam Ghaus Schodjaie, essayists in social philosophy.

The theatre, developing sporadically since the 1940s, enjoyed government support during the 1960s and 1970s, when a plethora of Dari adaptations of the plays of Anton Chekhov, Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams and Neil Simon appeared. The very small group of Afghan playwrights writing original material, led by Rashid Latifi (1906-1972?), active since the 1940s, and the younger Sayyid Moqades Negah (b 1925?), explored situations for social comment. Bureaucratic corruption and pseudo-sophisticated artificialities were favourite subjects of attack.

A free press flourished fitfully from 1965 to 1973. Newspapers carried poetry and short stories on themes ranging from Islamic conservatism to revolution, clothed in the form of traditional love songs and Sufi lamentations.

But political stagnation denied political parties legality and writers open expression. The literary movement lacked dynamism and meaningful direction when the monarchy was overthrown in 1973. The free press was stifled and a second coup d’etat in 1978 established the leftist Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, with Noor Mohammed Taraki as prime minister. A number of Taraki’s coterie from the 1950s and 1960s, including Suleiman Layeq and Bariq Shafiyee, took up prominent positions in the government, which promoted a style of socialist realism, relying more on polemical rhetoric than imagination or creativity.

After the Russian invasion in 1979 many of the literary elite fled into exile, where they combined guerrilla activities with reappraisals of the ideals they once expressed. Writers in refugee camps included Khalili, Abdul Ghafur Arezo (director of the Cultural Association in Iran), Kazim E Kazimi, Fazl Allah Godsi and Sami Hamed. Among those who remained in Afghanistan were Wasef Bakhtari, Ghahhar Asi, Parto Naderi, Haidery Woojudi and Azam Rahnavard Zaryab. These authors, as well as those who had fled overseas, wrote mainly about the sadness of exile. The most successful author in exile may have been Atiq Rahimi (b 1962) whose novel Earth and Ashes, first published in Dari in 2000, became a bestseller and was turned into a film directed by the author.

Since 2001 the focus of writing has been on newspaper and magazine production, publishing poems focusing on experiences of the past 20 years. New publications in the style of the epic stories and in the great literary tradition of the past are rare, and writers find it difficult to publish prose on subjects other than current social issues and politics. The most successful novels since 2001, The Kite Runner (2003) and A Thousand Splendid Suns (2007) by Khaled Hosseini (b. 1965), were written by an Afghan who emigrated to the United States at the age of 15. While these books have raised an interest in Afghanistan beyond the current war among readers worldwide, they have been controversial among resident Afghans.

Largely based on: Nancy Hatch Dupree, 'Afghan Literature', in Encyclopedia of World Literature in the 20th century, ed L S Klein (New York 1981, 2nd ed), pp 18-20.

Use the navigation bar on the right to make direct contact with organisations and individuals working in the literature sector.